| WWT Shows | CLICK TO: Join and Support Internet Horology Club 185™ | IHC185™ Forums |

|

• Check Out Our... • • TWO Book Offer! • |

Welcome Aboard IHC185™  Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Our Exclusive "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"

Our Exclusive "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"  IHC185™ "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"

IHC185™ "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"  CANADIAN Private-Label Watches

CANADIAN Private-Label Watches

Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Our Exclusive "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"

Our Exclusive "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"  IHC185™ "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"

IHC185™ "Timekeepers Photo Gallery"  CANADIAN Private-Label Watches

CANADIAN Private-Label WatchesRelated Content: Larry Buchan's ..."Tales from the Rails"

Go  | New Topic  | Find-Or-Search  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply to Post  |  |

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

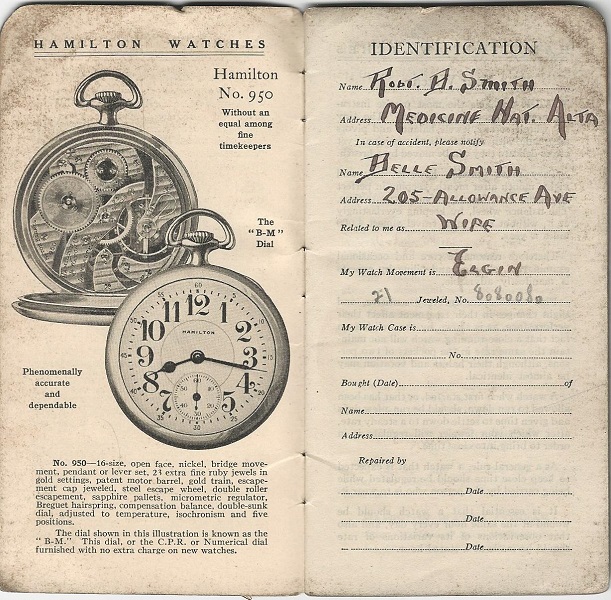

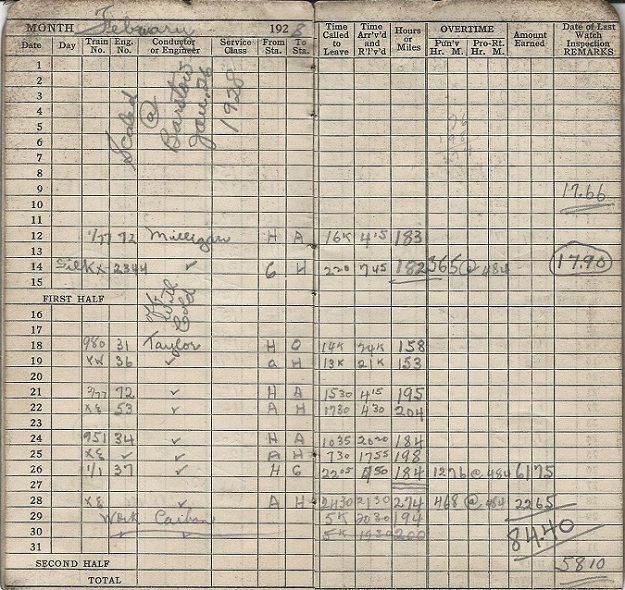

Hamilton time book 1928  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Time book February 1928  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

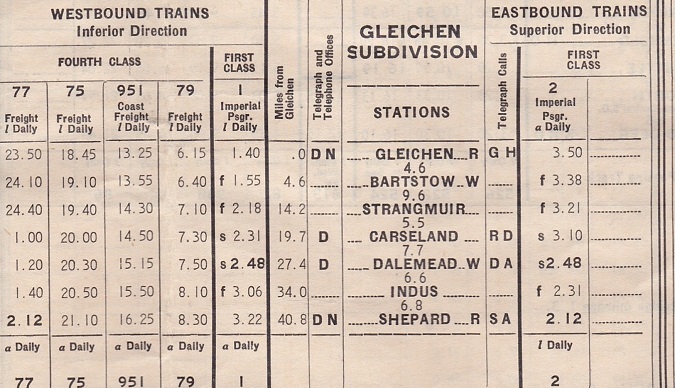

CPR Operating Timetable from 1925 showing the Gleichen Subdivision the Town of Bartstow 45 miles east of Alyth  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

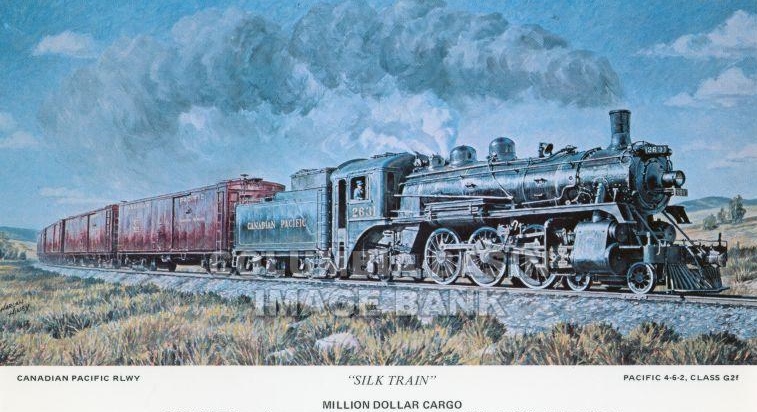

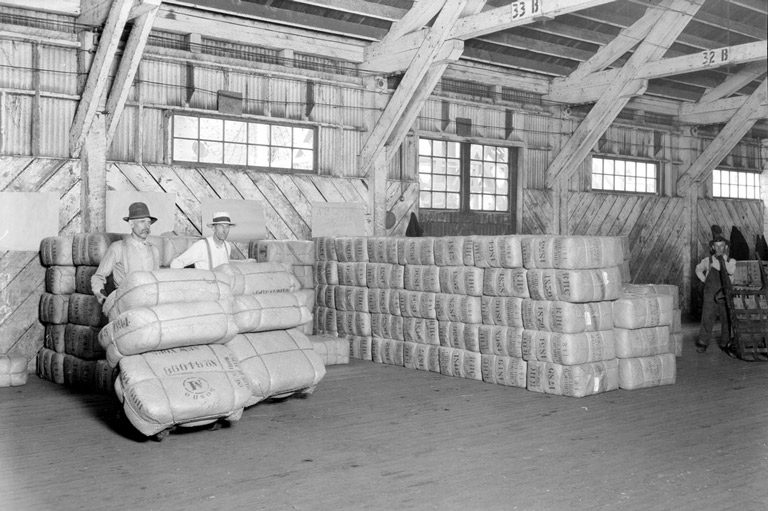

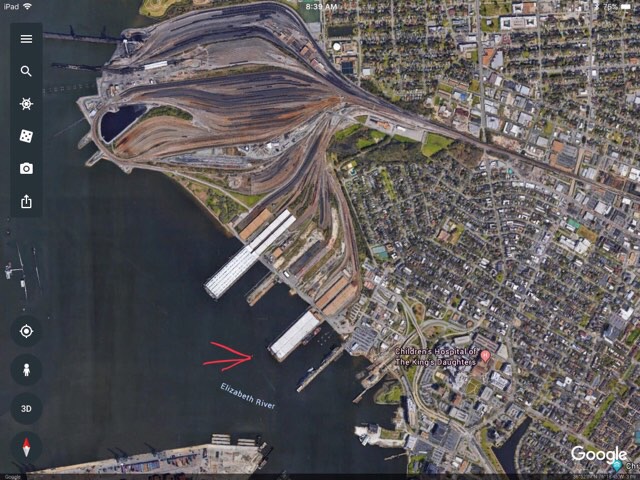

I found this in Canada's History: When Mary Lynas was in Grade 6 she and her classmates were Christ down to Canadian Pacific's train yard on the eastern fringes of Calgary to watch the spectacle that still captivates her as she remembers that early 1930s scene "That train came in at terrific speed" recalls the granddaughter of Col. James Walker, one of Calgary and Alberta's most influential early citizens. "They stopped only to put water in, change crews, and go again. The pitstop action Lynas is talking of was to service Canada's special silk trains that roared out of the port of Vancouver between 1887 and the late 1930s through the Rockies, across the prairies through the Canadian Shield to Montréal and Buffalo New York., Loaded with precious cargoes of raw silk from the Orient. Bound for the National Silk Exchange in New York and the mills of the eastern seaboard, the perishable silk, used to make luxury items like scarves, ties, shirts and dresses, was given the ultimate priority over all rail traffic, even express trains and, some said, Royal trains. Adding to the rush was the exorbitant cost of insurance. A bale of raw silk could easily fetch more than $800 in the 1920s. With about 470 bales to the car, a full train load was worth upwards of $6 million, and a lot of money in the days when a brand-new for cost less then a bale of silk. Insurance companies started the clock as soon as the bales were unloaded – rates were charged by the hour from the time the cargo left the boat until it was unloading at its eastern destination. The silk business was so lucrative for both Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railways that every minute count. Nothing was left to chance. Freight agents would often board a ship in Victoria and feverishly complete their paperwork so on the loading could start the second they talked at Vancouver. There, as soon as the ropes since the ship tied to the wharf, the race was on. The captain was on the microphone shouting orders. Silk bells were streaming off by a conveyor belt even before the passengers stepped on the gangplank. Stevedores whipped into action manhandling the 90 kg bales onto the dock and into the warehouse for waiting custom agents, who would clear them on the spot. Then the burlap wrapped 12" x 24" x 36" bales were wheeled onto specially built railcars, which were sealed and panelled with wood. The special cars were built shorter than normal boxcars to take curves at higher speeds. "They were totally different from the other freight cars, they had to be lightweight and fast," says Jonathan Hanna, Canadian Pacific Railway's corporate historian. Mounted on passenger car trucks [suspension and wheel systems], "they were solid, so they could put up with high-speed," says Hanna. At Vancouver, well before the ship approached, 8 to 15 of them were already coupled to an engine fired up to full steam, and engineer's hand poised on the throttle. Loading crew action was measured by the seconds per bale. For one eight car train, a typical regimen reported by CN was shipped docked at 15:42, commenced unloading and 16:13, train loading completed by 17:45 and train left dock at 17:52 – total time from ship tie up to train departure of 1 hour 39 minutes. Another reported an average time of 2.45 seconds per bale; anything less demanded an explanation to management. Train loaded, a couple of armed Railway police jumped aboard (although no robberies ever occurred) and with a blast of the whistle the engineer pushed the throttle forward. Smoke belching steam hissing, they'd roll out toward Hope. It was more than an express train. As the Vancouver, Daily Province reported on January 10, 1903, the silk train " makes the regular express time appear as but a snail's pace." The CPR silk train about which the newspaper was commenting had left Vancouver at 6 AM and reached Kamloops 248 miles northeast through the mountains, 10 hours and 45 minutes later – beating the regular express's time by a full hour. The silk business was so lucrative to for both Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railway's that every minute counted. Nothing was left to chance. Freight agents would often board the ship in Victoria and feverishly complete their paperwork so unloading would start the second they docked at Vancouver. Coming out of the mountains with their steep grades and tight curves that limited train speeds, throttles were opened wide on the straight lines of the prairies were speeds routinely were speeds routinely hit .93 mi. per minute and more. "Steam locomotives didn't have speedometers or governors like locomotives today," says Hanna "In those days you were supposed to go track speed which rarely exceeded 70 mph but you couldn't. say if you did or didn't because it was all in coming the time between mileage markers – if you knocked it off in 45 seconds that meant you were going 80 miles an hour. Sustained high speeds could be taxing on the locomotives and cars, so stops were made at every divisional point – about 125 miles apart. Except for the Brooks Subdivision that ran 175 miles from Calgary to Medicine Hat. It did not feel comfortable running them at speed with maintenance limited to a couple of shots of grease and some lube oil," explains Hanna. "There's so many thousands of moving parts, and roller bearing technology wasn't i around Yet." Pit stop times average about seven minutes. As a hot engine, hissed and squealed to a stop, it was quickly uncoupled and a freshly watered, fired up engine snapped on. At the same time, a "carman" was rushing around with his oil can, opening each journal box, shooting oil in and slamming it shut, then moving onto the next one. "It was all wonderfully exciting to watch" recalls Mary Lynas. Across the continent, silk trains followed no regular schedule, so it was an exhilarating moment to catch a glimpse as a flew passed unexpectedly in a cloud of cinders, smoke and steam. -5 Fresh crews took over at each stop. Silk train crews weren't particularly special – as it was not assigned passenger service, the work went to freight pool locomotive engineers and locomotive firemen that worked on a first in first out so it was luck of the draw to get a silk train that was half of the trip and you got home sooner – Steaming on through the Canadian Shield and south, CN silk trains completed their race against time crossing the border over the Niagara suspension bridge to Buffalo. There, U.S. Customs quickly sampled the bales (silk wasn't subject to important duties) and CN had the torch over to the New York Central Railroad, which made the dash to the finish line the Manufacturers Terminal in Hoboken, New Jersey. Across the continent, silk trains followed no regular schedule, so it was an exhilarating moment to catch a glimpse of the fabled trains as a flew passed unexpectedly in a cloud of cinders, smoke and steam. There was an intriguing myth that inside the bales silks were happily spinning their glossy cocoons as the trains sped across the country. That was pure table, however – silkworms spin their full cocoons in two or three days, after which silk harvest timing is critical. Despite all the rush, silk train accidents were surprisingly few. The only serious appearance was on September 21, 1927, when they car jumped the tracks as the train rounded a bend in the B.C.'s Fraser just east of Hope. Two our three cars followed it, sending silk bales tumbling into the river. There were no deaths and the cargo was salvaged. The first shipment of raw silk arrived at the port of Vancouver soon after the last spike of the cross-Canada ribbon of steel was driven. And €65 arrived on the afternoon of June 13, 1887, aboard the 3600-ton Abyssinia from Hong Kong, along with mail and 80 Chinese steerage passengers. When Canadian Pacific's fast Empress entered service, with their side ports for speedy unloading, Vancouver was vaulted into a leading silk port. On October 2, 1902, the Daily Province reported the s onto the steamship Tartar was due to arrive with 539 tons, or 2,156 bales of raw silk – worth $1.5 million. Just six days later the newspaper ran the headline "Large Cargo of Raw Silk," reporting that the Empress of Japan was due in with $1.6 million worth. On October 25, it reported "Vancouver, the silk port of North America: Over four and a half million dollars worth of raw silk will be received within 30 days," making October 1902 the highest value of silk shipping to date. In 1919, a CPR bulletin stated, "All records for silk handling were broken with the arrival from the Orient of the Canadian Pacific Steamship Empress of Asia... 10,000 bales of raw silk... Valued at$8,500,000..." The pace accelerated, and CP with its fleet of transpacific steamships maintain domination. Shortly after the full formation in 1923, Canadian National enter the fray with its first silk run in July 1925 CN made silk top priority too: there best time of 83 hours 56 minutes was almost a day faster than their transcontinental passenger train. But CN lacked the ocean shipping advantage, relying on British Blue Funnel Line or Japanese ships to bring in the raw product from the Orient. With two railroads putting silk traffic ahead of every other shipment, business boomed in the 1920s and the profits rolled in. What 1929 was tumultuous – silk shipments peaked, then came Black Friday in October, when stocks plummeted and the world fell into depression. Consumer demand flagged; luxury items such as silk were soon out of reach for most. Prices crashed – by 1934, raw silk was $1.27 a pound, down from the $6.50 a decade earlier. That precipitated a tumble in insurance rates, so speed became less of a priority and soon Japan was shipping silk in its own vessels through the Panama Canal, which had opened in 1914. The change was rapid: in 1928, 94% of all silk from the Orient to New York I crossed North America by train; just 6% went through the canal. Then, according to the B.C. Historical Quarterly of 1948, the Nippon Yusen Kaisha Steamship Line of Japan Started Panama service in 1929. Results for the railways were disastrous: by 1931. their share had dropped to just 40%; ships through the Panama handle the rest. The ships wooed business by dropping their freight rates to $6 a ton, $3 less than the railway's charged. CN Traffic Executive Officers held a series of meetings to look at the impact of matching the Panama shipper’s rates. Alas, the numbers were telling: based on 1929 silk tonnage, the railway would lose $211,902. Nevertheless, the reductions were made in 1931, but proved ineffective. Three years later they were back at $9. CP single-purpose silk trains in 1933, instead hitching two or three silk cars onto their regular trans Canada passenger runs. Trips for both railways continued sporadically until late 1930s, and by 1940 CN shipped just 504 bales. War with Japan was the final blow, killing all trade between the two countries. As well, the US government ordered all silk futures trading and production to cease as demand for silk changed from fashion runways to airfield runways – silk was used to make parachutes on the backs of aircrew members. But the silk trains have their legacy. "It the teacher us how to keep things fluid, which is what were still trying to do today, "says Hanna. "But now it's the question of insurance or perishability, it's just in time delivery for Walmart and the Bay and Zellers and Canadian tire. It still comes by ship load from the Orient and were still trying to get across the country as quickly as possible. What we learned from silk trains silk is that you've just got to keep it moving." Today, CPR's last remaining silk car of 46 built sits forlornly in CPR's Ogden Shops in southeast Calgary, just a few miles south of where Mary Lynas and her friends played. "But it's not in the shape of a silk car anymore," says Hanna. "It survived because we first converted some of the some of [the silk cars] into mail express cars and then in the 1960s we took five them and converted them into robot cars that took radio signals from the head end to tell the mid-train power what to do." This one survived because it was converted to carry an experimental steam generator as a novel way to kill weeds along with the rights of way in B.C. "This ex-steam generator, ex-robot, ex-express, ex-silk car is the only one left. Here is a view of a CPR steamshiph hold with Long shoreman ready to on load the bales of silk.  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Silk bales on the dock  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Bales of silk in the customs Warehouse  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Silk Train in Vancouver  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Silk Train departing Vancouver  | |||

| IHC Member 1541 |

Larry, No doubt this was a bit of a ruse during the war as the enemy would not want to attack fish or silk trains but here is a bit on “Fish” and “Silk” trains from the book Trains of Recollection (1924) The author, D. B. Hanna was with the CNoR from it’s early days and named president of the reorganized company in 1918. He was appointed first president of the Board of Directors of the Canadian National Railways in 1919. “Fish trains” carried British gold to be minted at Ottawa, most of it to be sent to the United States to pay for war material. “Silk trains” carried Chinese coolies who were brought across the Pacific to work behind the trenches in France and Flanders. Between July, 1917, and April , 1918, sixty-seven “silk trains’ entered Halifax carrying 48,708 coolies. But the coolies, even when they could be kept behind blinds, were not as interesting as the boxes of gold, of which the public knew nothing, and about which observers along the route were mystified indeed. Warships brought to Halifax gold cargoes each worth from ten to twenty million dollars. The average sized “fish’ special consisted of six baggage cars (the first as a buffer behind the engine, and accommodating guards, and a private car, in which were railway officials. At night an armed guard rode on the engine. Through a train telephone, notice was given of anybody having authority to pass through the cars. The most precious “fish train” was of eleven cars, holding sixty seven million dollars. A wheel tapper at a division point said to another, “I wonder what kind of a train this is, with so many baggage cars and no passengers.” | |||

| IHC Member 1541 |

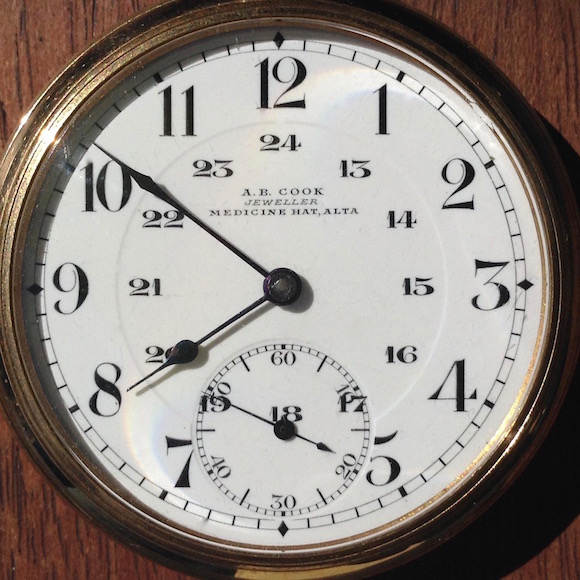

Regarding the time book you posted earlier, A.B. Cook Jeweller Medicine Hat Alta. marked only on the dial. 16s Regina movement #5140160 (1916) 15j  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Thanks Lorne for posting the interesting information on the CNoR silk trains and gold shipments. Also the photo of the A.B. Cook, Medicine Hat Pvt. label Regina private-label dial | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

I have a Hampden 18 size, 23 jewel movement with a Canadian Pacific open face dial.Lorne Wasylishen found me a Hampden with a 24 hour dial the movement was marked Canadian Pacific they look very good together thanks Lorne.  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Dial with bezel off  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Picture of 15 jewel Canadian Pacific movement. | |||

| IHC Member 1541 |

They look good together Larry, I may be just a titch jealous. | |||

| IHC Member 2030 |

Very easy to read dial Larry . Your pic of a CPR steamshiph hold in August reminds me of unloading rubber bales from Indonesia and cocoa beans from Columbia at the N&W merchandise piers. Oh and coal  | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

I had been looking for a Canadian Private Label marked Medicine Hat for over 40 years and I finally found one marked “J.D. Stoddart Medicine Hat on a single sunk Arabic 24 hour dial. It is an Elgin, 18 size, 21 jewel, Open Face, Serial No. 8980823, a Grade 252, marked Father Time, manufactured in 1899, Nickel plates, and cased in an American Watch Case Co. of Toronto, Ontario, Fortune yellow gold filled case. I had worked out of that terminal in the winter of 1973-1974 working as a spare board brakeman on freight from Medicine Hat to Alyth yard in Calgary, and East to Swift Current, Saskatchewan. I worked as a locomotive engineer running freight from Alyth to Medicine Hat,and passenger trains from Calgary during the last 10 years of my career. I have attached some photos of me on a westbound freight sitting in the siding at Bowell, the siding was named after Sir McKenzie Bowell served as Canada's prime minister from December 21, 1894 to April 27, 1896. waiting for an eastbound to arrive. Photo 6 me at the throttle our train is clear of the main track. Photo 5 a map of the Brooks subdivision Photo 6 me at the throttle of the 9513 Photo 7 a view of the 9513 it is painted in the dual flags livery. As the CPR had bought the old Milwaukee Road track into Chicago. Photo 8 me getting off the engine to give the eastbound 9106E a pull by inspection. Photo 9 of the 9106E arrives. | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Photo 1 the dial on my Canadian Private Label, the dial is marked "J.D. Stoddart Medicine Hat" | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Dial with bezel off | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Elgin Father Time movement | |||

| Railway Historian IHC Life Member Site Moderator |

Case Trademark | |||

| Powered by Social Strata | Page 1 ... 47 48 49 50 51 52 |

| Your request is being processed... |

|

©2002-2025 Internet Horology Club 185™ - Lindell V. Riddle President - All Rights Reserved Worldwide