| WWT Shows | CLICK TO: Join and Support Internet Horology Club 185™ | IHC185™ Forums |

|

• Check Out Our... • • TWO Book Offer! • |

Welcome Aboard IHC185™  Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers

Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers  Pocket Watch Discussions

Pocket Watch Discussions  Transitional Illinois

Transitional Illinois

Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers

Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers  Pocket Watch Discussions

Pocket Watch Discussions  Transitional Illinois

Transitional IllinoisGo  | New Topic  | Find-Or-Search  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply to Post  |  |

| IHC Life Member Certified Watchmaker |

I would like to ask a few questions about a transitional Illinois. I enclose a few pictures of a nice example I recently acquired. The serial number 415089 that I make to be 1882 Size 18 and as you can see in great condition and running, it is a stem wind lever set, but also hence its name also retains the key wind function, why? As this would cost more to produce as opposed to a later blank plate why would they retain this option, is it just a over run of parts/plates. Chris Abell  | ||

|

| IHC Life Member Certified Watchmaker |

P 2 Chris Abell  | |||

|

| IHC Life Member Certified Watchmaker |

p3 Chris Abell  | |||

|

| IHC Life Member Certified Watchmaker |

p4 Chris Abell  | |||

|

| IHC Member 163 |

Thank you Chris. If your dial had the script Illinois Watch Co., in the same style as the old Hamilton Watch Co. lettering, you've just posted photos of my 7j Illinois transitional 18s I wrote about receiving for Christmas, but had no way to post photos. I have been told that these existed because at the time many people did not trust the pendent wind function of the watch when it was introduced. Sort of like when automobiles first offered automatic transmissions over manual shift. Fluid drive transmissions were the 'transitional' function of that industry, as though it functioned like an automatic transmission, you still had to use a clutch to engage it. Folks can be slow to embrace an idea, and this (as has been explained to me) is just one of those examples. Regards. Mark NAWCC Member 157508 NAWCC-IHC Member 163 | |||

|

Chris, It is believed that the transition movements were as they are (both kw,sw) for 'ecomomy' reasons. to use up perfectly 'good' components. | ||||

|

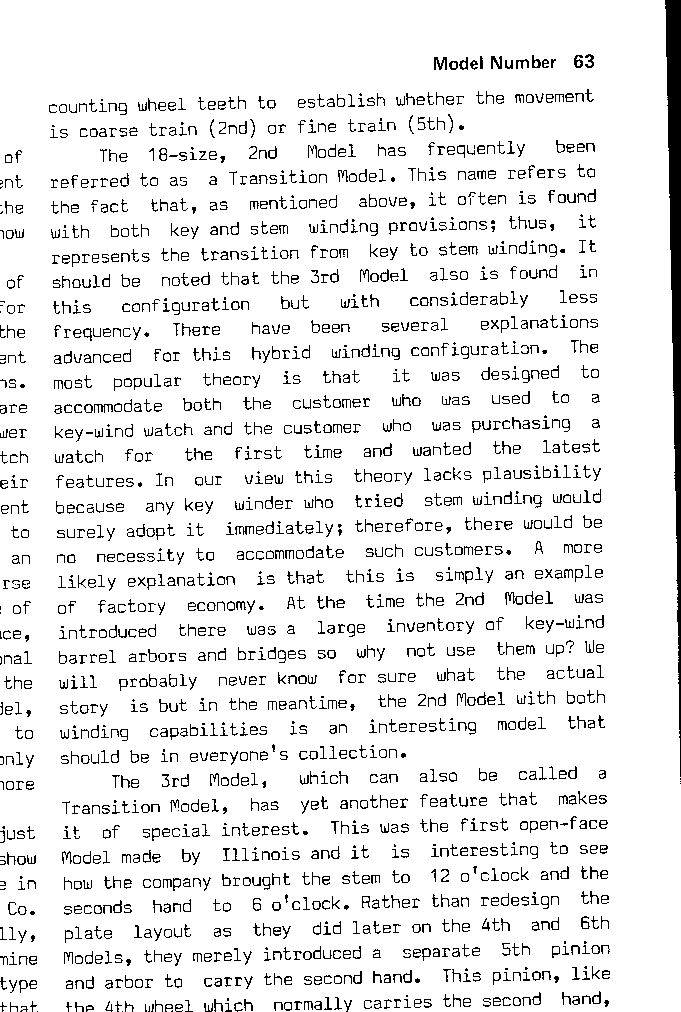

Here is an opinion by the Late Bill Meggers, from his 1985 book on Illinois watches.  | ||||

|

| IHC Life Member Certified Watchmaker |

Thanks for all the responses and the last from Meggars, interesting to read that it is considered to have been a matter of using up old parts, but don’t you think that this would have been seen for what it was, and may have lost sales doing so, instead of switching straight to the new improved sleek design in a highly competitive market. Would you want a crank sticking out on your car because they had a few left over? Guess we will never know but a interesting addition for collecting. Chris A | |||

|

quote: i couldn't agree more..... | ||||

|

| IHC President Life Member |

Great topic guys! I love being able to scroll through something like this. Very cool all the way through. | |||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

I've frequently heard it explained that watch companies had "huge stockpiles" of movement parts, but that doesn't make sense to me. Why would they? Why wouldn't they just make enough parts to satisfy the existing demand, rather than investing capital in labor and materials to stockpile large quantities of parts that weren't needed? Today, parts for exotic high-grade Swiss watches are difficult to obtain because the companies are using all the parts they can produce to make new movements. There aren't any spare parts, and there never have been! I personally think the explanation for "transitional" watches is more like Mark originally explained, and was to satisfy a certain type of customer (such as the British, who preferred key-wound watches even into the early 20th century). When stem-winding was new, people who'd been winding watches with keys for 60 years didn't fully trust it. A customer might say: "What if it fails?" In which case, the sales clerk could reply: "In the very unlikely event that happens, you can still wind it with a key, just like your old watch..........." When automobiles were first fitted with electric starters and batteries, people didn't fully trust the reliability of those, and cars were fitted with both electric starters and hand cranks for several years. By and large, the cranks probably did more to "comfort" the purchaser, than they did to serve a practical purpose, but if they helped sell automobiles to otherwise reluctant purchasers, that was purpose enough to justify their production. I rather doubt that the presence of a key-winding arbor would have prevented a late 19th century customer from purchasing a particular movement, but the lack of one might have caused reluctance on the part of a few customers, thereby justifying their production. Of course, that's just my opinion, but I'd bet it's right. ============== Steve Maddox Past President, NAWCC Chapter #62 North Little Rock, Arkansas IHC Charter Member 49 | |||

|

Points taken, but...... in this time frame, was there not a "recession" of the economy? What if "projected" sales and production figures were not obtained....... that would result in parts, movements, etc. being unsold We also know from some production records that not 'all' movements were completed in 'numerical' order ***for example the "re-numbered" hamilton movements in the 30k serial range {i cannot come up with Illinois examples without digging in materials... sorry} Another example was the practice of Illinois to add the fifth pinion to make the existing Hunter case movements into open face.... I do think both theories have validity, and the other opinion in todays terms would be from a 'marketing' department decision...but because of stockholders, and need for profit.... I sway toward the "use of existing stock" theory. Also in a production environment, the 'old' school of thought was to make a component in quantity, therefore reducing the unit cost.... There did not seem to be a Just In Time or Kaazan (sp?) mentality then. | ||||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

Terry writes: "Another example was the practice of Illinois to add the fifth pinion to make the existing Hunter case movements into open face......" Actually, "fifth pinion" models weren't created to utilize existing stocks of hunter movements, they were created because the companies that used them hadn't yet developed any true open face models. Once true open face models were developed, the fifth pinion models were immediately discontinued. I'm sure that production in the 19th century was different than it is today, but I can't see any reason that some principles wouldn't remain unchanged. For example, let's suppose that a particular employee at a watch factory was responsible for operating a machine that made barrel bridges. Furthermore, let's assume that the fellow could produce 500 barrel bridges per day, at a time when the factory output was only 250 movements per day. It's easy to see that by the end of a week, the fellow would have produced enough barrel bridges for two weeks worth of watch production, and no company would have allowed that situation to continue indefinitely. Sooner or later, they'd have assigned the fellow a different task, or laid him off until stocks of existing barrel bridges started to run low. As far as I can see, there should never have been any advantage to having thousands and thousands of excess parts of any particular type; the companies wouldn't have wanted to store them, nor to have the financial investment in parts that weren't going to be used in the near future. As for recessions and economic fluctuations, those did occur from time to time, but I'd be greatly surprised if they can account for all the various "transition" models produced by the several different companies that made them. I don't have any facts and figures in front of me at the moment, but it seems unlikely that all "transition" models were produced at exactly the same time, which is what would have been necessary in order for an economic explanation to be plausible. Again, I don't know for certain myself, I'm just attempting to apply sound reasoning......... =================== SM | |||

|

I favor the theory that Illinois (or any other company with "transitional" watches) was just using up parts already made. Steve said " quote:This was the big difference between the American way of manufacturing and the Swiss way. The American companies wanted a stockpile of spare (interchangeable) parts on hand to last for all future demand. The Swiss, without comparable interchangeablitily, would have been foolish to make large quantities of parts. (Don't forget, we are talking about the late 1800s for these old keywinds). I believe it was cheaper to make extra parts while the machinery was set up than to constantly reset the equipment for small production runs. A watch factory generally finished watches in groups of ten. They probably made them in groups of up to a few hundred at a time. However, they did not make the component parts in such small number. There was not one machine set up exclusively for making 18-size barrel arbors. The automated machinery probably needed to be set up for each job and they would make a large quantity of parts while they were at it. In an 1884/85 publication describing the production of watches at Waltham, the writer describes seeing, for instance, a box containing over 19,000 center wheels. He also saw a jar contained 10,000 second hands -- one days production of a monthly order for 160,000! At the time of his visit, pinions for 100,000 watches were in process. Obviously the factories at this time set up the machines and then made more parts than they needed for immediate production. The next day or week the machine was reset to produce parts for a different model. In this fashion I feel fairly certain that Illinois had many barrel arbors on hand for keywind watches, and when they switched production to stem wind models it was obviously more economical to use up what they had in stock before setting up the lathes for a new run of arbors. | ||||

|

quote: Steve, I can agree with the above wording.....but the fact remains they used an existing Hunter movement (or parts) to manufacture the Open face movement, which used this inventory. Thanks Jerry for the 1800's info on production numbers. This type of production seems to have been the 'standard' for many years, not only in watches, but many items such as auto parts and guns. | ||||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

In my message above where I wrote: "Today, parts for exotic high-grade Swiss watches are difficult to obtain ....." By "Today," I meant "now," as in the "present time." At this very moment, essentially a century after the "American system" of manufacturing was adopted in Switzerland, parts for new high-grade Swiss watches are essentially nonexistent because all the parts that can be produced are being used in current production. There are no "spare" parts, and never have been, and that situation is not caused by lack of interchangeability, it's caused by factories operating at full capacity. Many of the essential machines used in American watch factories were in fact not "set up" to perform certain tasks, or to make certain parts. In order for that to have been possible, the machines would have had to be versatile enough to perform a variety of different tasks, and that often wasn't the case. Many watch part producing machines were designed to produce just 1 part, and they were entirely "dedicated" to that purpose. Although it might have happened in some cases, it would not have been common that the same machine that made barrel bridges for one model, could be "set up" differently to make barrel bridges for another. Of course, I'd think it's obvious that an automatic screw machine could be "adjusted" to produce different types of screws, and that a damascening engine could be "adjusted" to produce different damascening patterns. The same was probably true of machines that made pinions, and perhaps for machines that made some other parts, but in most instances, the machines used to make pillar plates, barrel bridges, top plates, pallet forks, and many of the other principal parts, were "dedicated" machines that were designed and built to perform just 1 particular task, and nothing else. As for the notes about "fifth pinion" models, the same concept is very much related. In order for a company that had been producing exclusively HC movements to switch to OF production, MAJOR modifications were necessary. First, engineers and draftsmen had to design a workable OF model that didn't infringe on any other companies' patents. Next, mechanical engineers and draftsmen had to design the machines necessary to produce the parts, and finally, highly skilled tool and die makers had to actually create the machines using the blueprints provided by the engineers. Needless to say, that process required a huge investment in both time and money, and some companies chose to create "fifth pinion" models, at least as a stopgap measure, so that they could produce and market an OF model with minimal time delay and minimal investment, while using the same dedicated machinery that had been producing HC models for years. Again, it wasn't just a matter of "adjusting" a machine that had been making pillar plates for HC models to instead produce plates for OF models; entirely new and different dedicated machines had to be designed and fabricated, and that's one of the main reasons most watch companies produced the same designs for decades before changing. "Fifth pinion" movements were never intended to "convert" HC inventory into OF models, they were designed to meet the emerging market for OF models with minimal delay and minimal capital expenditure, and were made so that the existing machinery could be used, not the existing inventory. ================== SM | |||

|

In my opinion, Terry and Jerry are on the right track. Until recently, the American method of manufacturing was to minimize part cost by running "economic order quantities" of parts. By running large quantities, the individual machine setup costs are amortized over a large number of parts. In most cases, this method of production results in high inventories at the component level. To minimize excess and obsolete parts that would have to be scrapped as models changed, it is very likely that manufacturer's would find a way to use as many of these components as possible. In the recent past, American manufacturers have learned that they can no longer be competitive using these strategies. By finding ways to reduce and eliminate setup times, manufacturers now strive to run minimum lot sizes based on actual demand. Rhett Lucke | ||||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

Mr. Abbott was an influential figure in the evolution of the American watchmaking industry in the late 1800s, and for anyone who's still confused about how and why "transitional" and "fifth pinion" models were created, perhaps the following information from him will be informative: " About the year 1880, the several American watch companies discontinued the manufacture of key-wind watches and importers stopped bringing them in from Europe. There were, however, a number of key-winders still in use. Those of the better grades were likely to remain in use for many years and their owners were easily persuaded to pay the cost of having them converted into stemwinders, since the watches would then be not only more convenient but fashionable. Ours was the only shop in the country which made a specialty of that kind of work. It, however, was still very costly because it was necessary to make and fit each part separately. In 1880, I put on the market a winding device that was so designed and constructed that it could be attached to a watch while completely assembled. These were manufactured in quantity for all the different models of American watches. Specifications were prepared and printed in such manner that workmen of average skill could, with these devices, convert from a key-winder to a stem-winder any American watch. More than one hundred thousand watches were converted by these devices or "attachments." About this time fashions in watches changed and open face cases were in demand. For many years, only closed case or "hunting case" watches were made and sold. The logical place for the stem or pendant of a closed case watch is opposite the figure three of the dial. In an open case watch the proper position for the pendant is at the figure twelve on the dial. Manufacturers and dealers tried to persuade the public to buy open case watches with the winding stem entering the movement under the figure three on the dial, the same as in hunters, but the wearers of watches would not have them that way and very few could be sold. At this stage in proceedings, at the urgent request of many watch dealers, I designed and made [a] winding mechanism specifically adapted for open face watches and utilized all of the unsold key-wind watch movements in the stocks of dealers in the larger cities, by making them into fashionable open face watches. The Rockford Watch Company got out their tools and made new made new key-winders which they sent me for conversion. Several thousand of these converted watches were sold while other manufacturers were making tools and getting ready to meet the demands of fickle fashion." ----------------------------------------- Obviously, if Rockford "got out" their old machinery for making key-wind watches, and made new runs of those with the intention of adding Abbott attachments to them, that clearly indicates the machinery that had been used in the production of KW models was no longer in use. Indeed, as was the customary practice, when Rockford began production of their new stem-wound hunting cased movements, new machinery was created specifically for that purpose, and the old machinery for producing KW models was placed in storage. Furthermore, Mr. Abbott's statement that: "Several thousand of [the converted Rockfords] were sold while other manufacturers were making tools and getting ready to meet the demands [for OF watches]," clearly indicates that then, as now, time was an important factor in marketing new products. The first company to fill a new demand, became the first to sell a lot of new watches, but in order for a watch company to produce a new and different model, new and different machinery typically had to be created, and that caused a delay in production. Obviously, "fifth pinion" conversions were a way of using the same machinery that had been producing HC movements, to produce new OF models and get them to market ASAP, thereby avoiding delay and the resultant loss of market opportunity. Even though the evidence is clear, I imagine some will still cling to the old misconceptions, and the "debate" will continue for years to come, just as it has over years past. Personally, I'm about as certain of the reasons that "transitional" and "fifth pinion" watches were produced, as I am that the world is spherical instead of flat, but I'm resigned to the fact that those who've convinced themselves otherwise are going to continue clinging to their beliefs, regardless of whatever evidence is produced to the contrary. My only hope is that people who haven't yet formed an opinion, will avoid learning a misconception. ==================== SM | |||

|

| IHC Member 163 |

Steve, this was the first time I've ever read that watch companies tried to convince the public to accept hunter movements in open face cases! I've always read and/or been told that these were just hunter movements sold in open face cases because the hunter case had been sold at an earlier date, and that none had ever actually been cased this way by a factory. Very interesting. Thank you! Regards. Mark NAWCC Member 157508 NAWCC-IHC Member 163 | |||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

Mark, The subject of originally cased "sidewinders" has been discussed here before on a number of occasions. https://ihc185.infopop.cc/eve/forums?a=search&reqWords=sidewinders ====================== SM | |||

|

| IHC Member 163 |

Oh, I'm fully aware of the discussions regarding 'sidewinders', and read most of them as I have had the time. As I recall, the term 'sidewinder' has usually been used with distain as referencing a watch that had been recased in an apparent incorrect configuration by a secondary seller....specifically a hunter movement into an open face case,or more recently an open face watch in a HUNTER case. (not sure what you'd call THAT creation. NAWCC Member 157508 NAWCC-IHC Member 163 | |||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

As further evidence that "transitional" movements were not created merely to use excess parts originally made for key-wind models, consider the parts numbers provided in the 1893 Otto Young & Company, as well as the 1900 Benjamin Allen & Co. catalogs. Both show listings for "Illinois, 18 Size, Full Plate, Key and Stem Wind" (which means either KW only, or "transitional"), with separate part numbers provided for the barrel arbors of key-wind and stem wind models. Parts for other 18s Illinois models are listed in different sections on different pages. The same situation is repeated in the sections for Rockford, Hampden, Keystone, Lancaster, Melrose, etc., in each case with different part numbers provided for the barrel arbors used in KW and SW models. In no instance is a barrel arbor shown as "key or stem wind," nor is the same part number indicated for the different configurations. Furthermore, in the E. & J. Swigart & Co. "Illustrated Manual of American Watch Movements," page 78, a full list of parts is provided for "18 Size Illinois - First Model, Key Wind and Setting." The part numbers of the barrel arbors are 512 and 513 (presumably for low or high grade models). Beside that listing is another that says: "Second Model, Hunting, Lever Set, Coarse Train" (that would be the "transitional" models). The listing goes on to say: "The changes from the 18 size first model to the second model material are as follows," then a list of about 45 parts is provided, among which is the "Barrel Arbor," part number 81. Again, this is clear evidence that "extra" key-wind parts were not used in the "transitional" movements. "Transitional" models required a variety of unique parts that were specifically made for them, and nothing else, but they did use the same basic design and plates as key-winds, and therefore could be produced using much of the same machinery. That's the reason the "transitional" models were created, not merely to use "excess" parts from older models. We can only speculate about why the companies chose to leave the key-winding arbors and cups on the new stem-wind movements, instead of simply dispensing with those parts, but I still contend it was to accommodate as much of the market as possible. Afterall, there is no disadvantage to being able to wind a watch either way. ================ SM | |||

|

As stated earlier, I believe Terry and Jerry were on the right track and my previous post was to meant to provide background on how manufacturer's in the past(including watch companies) ended up with large and unbalanced inventories. Many American companies continued with these inventory practices well into the 1980's. Having said this, I would suspect that the whole story behind the "transitional" movements is much more complicated. I would guess that the desire to develop and introduce stem winding models quickly, along with the need to keep down capital costs (by not completely retooling) also may have played a part. In the end, we can only speculate (as I suspect Mr. Abbott may have done along with Bill Meggers and others) as to the full story behind these watches. Rhett Lucke | ||||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

Rhett writes: "I suspect Mr. Abbott may have [been speculating] as to the full story......" I can't say with absolute certainty that he wasn't, but I can say that if he was, he wouldn't have needed to because he had first hand knowledge of the subject. In brief, Henry G. Abbott was born on June 24, 1850, in Dansbury, CT. His home town later named their State Vocational School in his honor. In 1866, at the age of 16, he embarked on his career in the watch industry, and was first employed as an apprentice watchmaker in a large repair shop in Newark, NJ. At the age of 21, after five years of experience and a promotion to Manager of that firm, he left to open his own shop on Maiden Lane in NY City. In 1871, Mr. Abbott was introduced to Edward Howard, who is generally recognized as the father of the American watchmaking industry. From that time onward, Mr. Abbott's firm cased all of the E. Howard movements that were distributed throughout the country. Although Mr. Howard was nearly 40 years Abbott's elder, he recognized the genius of the 21 year-old man, and the two men had a close personal and business relationship that was lasted for the rest of Howard's life (and Edward Howard lived to be 91). During his life, Mr. Abbott was awarded over 40 patents. Most of his earliest pertain to stem-winding attachments for key-wind movements, but he also received 9 patents for advances in the production of porcelain dials, a number for early typewriters, telephone meters, telephone call recorders, eyeglasses, and a plethora for machinery for watch factories. He designed a gear and pinion cutting machine which is sometimes still used even today, and his method for designing and making fly cutters for gears and pinions was so revolutionary that it was published in the August 25, 1910 edition of "The American Machinist." In addition to his other efforts, Mr. Abbott authored at least two books, "The American Watchmaker and Jeweler," © 1893, and "Recollections of Elapsed Time," © 1931. He was also Treasurer of the National Association of Manufacturers for nearly 20 years, and in December of 1943, he was honored by that Association at a gala banquet at the Waldorf Astoria. Unfortunately, the weather was bad at the time, and he caught pneumonia which resulted in his death on December 18, 1943, at the age of 93 years and 6 months. Again, I don't know for certain that Mr. Abbott wasn't merely "speculating" in his accounts of the evolution of the American watchmaking industry, but I rather doubt it. Indeed, despite the fact that parts lists and contemporary accounts both indicate otherwise, it's entirely possible that the people who think entire runs of movements were designed and produced to utilize excess production of obsolete parts from previous models are right, and Mr. Abbott simply didn't know what he was talking about. I wouldn't bet my money that way, but I do acknowledge that it's possible. ========================== SM Steve Maddox Past President, NAWCC Chapter #62 North Little Rock, Arkansas IHC Charter Member 49 | |||

|

I thought that would get a response Rhett Lucke | ||||

|

I have done some research into this part of American watchmaking and I used to have some contacts at Hamilton when I lived in Lancaster. Everyone here is essentially right. Also the reasons stated are why the American industry fell away. In the early days most manufacturers made basic calibers in lots of ten or more and placed them in inventory. The other parts, such as wheels, escapements etc were made in larger lots depending on the selling trends and demand. What would frequently happen and why identification is so much fun is the calibres would be retrofitted depending on fit and viability. This would create movements with normally never seen make ups. As production commenced running changes would reflect the updated product and at times older calibres would be used for spare parts or not at all. This happened more frequently than the manufacturers liked and created financial problems. The American industry had the right concept, the Swiss simply took it to the next level and gained control. Viele Grüße David Fahrenholz Fahrenholz Clock & Watch Timeless Service | ||||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

In contemplating the reasons for the production of "transitional" and "fifth pinion" watches, the most important factor to consider should be the most obvious: The element that allowed the American watchmaking industry to dominate world production, was the ability to produce mass quantities of inexpensive parts by automated machinery. No American watch company would ever have allowed their new production to be governed by the inventory of parts left over from older models. Parts produced by machines were incredibly cheap, and companies wouldn't have given a second thought to tossing them out by the thousands, just as they did every time a machine went wrong and inadvertently produced several thousand defective parts before anyone noticed. Then, as now, the principal costs of any manufacturing operation were machinery and labor, and labor didn't become a significant factor until final assembly. Indeed, the primary cost of parts production (both in time and expense) would have been the machinery itself, and that's what dictated production and model changes, not the inventory of parts on hand. ==================== SM | |||

|

| IHC Member 179 E. Howard Expert |

Steve,your statement that Mr Abbotts firm cased all E. Howards from 1871 on certainly doesn't ring true according to the factory records. There were dozens of different casemakers for Howard movements, which were sold un-cased to a large number of various wholesalers , many different wholesalers had their own trademark, that particular part of Mr. Abbott history that he cased all Howards just isn't so. Where did you find that erroneous info? Harold | |||

|

Steve, Just to clarify. Manufacturing costs are usually broken up into the following categories: 1. Overhead (both variable and fixed): Includes machinery, equipment, buildings, supplies, benefits, etc... Benefits obviously being a much smaller portion in the late 1800's than today. 2. Material: Both raw material and purchased parts. 3. Labor The cost of any given part is made up of it's material cost, labor cost and a portion of the overhead which is usually allocated based on the labor content. Over time, labor has actually been the smallest portion of the total cost. Every operation varies, but in most cases, the labor content is usually less than 10% of the total cost. Material and overhead are usually the main drivers of part and inventory costs. In the interest of not boring everyone to death, I'll quit here. Maybe a few members could post some pictures of these "transitional" movements which started the conversation. My personal favorites are the private label examples. Rhett Lucke | ||||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

Harold, I don't think the statements attributed above to Mr. Abbott are erroneous, I think you just misinterpreted them. There is no evidence that Mr. Abbott's firm ever produced cases, they simply fitted movements into cases that were produced by other firms. Furthermore, as I understand it, Mr. Abbott didn't claim that his firm cased every Howard movement sold after 1871, only that his firm held the exclusive contract to case all the Howard movements that were sold as complete watches in the US after that time. If I wasn't clear about that in my previous message, I do apologize. In any event, the information above attributed to Mr. Abbott was largely taken from the February 1961 "Bulletin" #90, pages 584 - 591. The specific article, entitled "A Vignette... Henry Abbott, Horological Inventor Extraordinary," is the written transcript of a speech presented to a New Jersey Chapter, by William C. Moodie, Sr., who knew Mr. Abbott personally. A portion of the pertinent part begins on page 586, column 2, paragraph 2, and reads as follows: "He [Mr. Abbott] credited Edward Howard with being the father of watch manufacturing in the United States. His acquaintanceship with Edward Howard started in 1871 and they were friends from the first. He had a contract with Edward Howard to case all his watches in New York before they were shipped throughout the United States. Most of these watch cases were made in Brooklyn. Howard's watches were of high quality and were high priced. During their long years of friendship, he and Mr. Howard became fond of each other and when Mr. Howard was past 80 and retired, whenever he visited New York he would often spend hours beside Henry Abbott's desk reminiscing about his struggles of earlier days............" -------------------- Rhett, Mr. Abbott was apparently an officer in the "National Association of Manufacturers" for a number of years, and I would think he knew quite a bit about manufacturing. I myself know very little about the subject, but I do know that the production of watch parts cannot be appropriately compared to the production of appliances, automobiles, or any other typical mass-produced item. According to the United States Tariff Commission's Report # 20, "Watches," © 1947, page 33, paragraph 2, "Labor costs represent the greater part of the total cost of producing watches." That statement tends to indicate that either the United States Department of Labor didn't know what it was talking about, or the figures you reported above pertaining to general manufacturing expenses, do not apply to the production of watch parts in the United States. The report goes on to say that due to the specialized nature of the equipment: "From 80 to 90 percent of the watchmaking machinery in use today in the United States, exclusive of that in the Bulova plant, was made by the individual watch manufacturers themselves." Further, it describes the "learning period" of the craftsmen employed at the various American watch manufacturers as follows: Die makers - 6 years; Tool makers - 4 years; Machine makers - 4 years; Machine repairmen - 3 years; Machine operators - 1 year. The "learning period" is defined as: "The length of time required before a worker's piece rate of pay equals the company's minimum hourly rate of pay." In short, while labor constituted the greatest portion of the overall production cost of American watches, even after World War II, that wasn't due to machine operators and assembly workers, it was due to the highly skilled craftsmen and specialists who were required to fabricate and maintain the machinery. Production and maintenance of the machinery itself was ultimately the most significant expense, although that cost in turn was due to the requisite highly skilled workforce. If watch parts themselves had been expensive to produce, I could accept the idea that new models were designed around existing inventory, but automated machinery allowed them to be produced so cheaply that tens of thousands of them could have been discarded for less than the cost of fabricating and bringing a single custom-made machine into operation. Again, it's my opinion that the reasons "transitional" and "fifth pinion" movements were produced had everything to do with machinery, and nothing to do with excess parts inventory, and it seems to me that my opinion is supported by a number of authors, experts, and other sources, over a wide range of years, but if I'm proven wrong, it certainly won't be the first time, and it probably won't be the last. I'm sorry if I've bored anyone, but I do hope that those who've persisted in debating this subject will either attempt to offer some documentation and supportive evidence for their opinions, or else stop perpetuating an idea that cannot be supported by facts. =========== SM | |||

|

| Watch Repair Expert |

The image below shows a Rockford "transition model" from my collection. I suppose it's a model 2, as it's a HC/SW/LS, but the serial number in the 16k range seems unusually low to me for a model 2. The dial has pinned feet, and although the lever operates back and forth like a switch, instead of pulling out like an ordinary set lever, it doesn't appear to be an Abbott's conversion. The surprising thing to me is the way the movement is designed, with the spring barrel almost directly opposite the fourth wheel. There's no way a movement of that type could be converted into an OF model (the stem would have to pass horizontally through the spring barrel), so perhaps Mr. Abbott had some of his facts confused. Was he an horological genius and an historical pinhead? =================== | |||

|

Steve, Your line of thought is logical. In specialized products labor is a big cost of the finished product. Therein lies the rub. Investors and shareholders expect and recieve an accounting of durable goods, including raw material, purchased assets and buildings/land. A company needs to show production material as a seperate entitiy to enable them to write up or down the cost of such material or inventory. In most cases you pay taxes on this material and it behooves you to manage your inventory well to minimize this. What a lot of "early" companies did was to create loss in materials to show investors that their managerial skills were intact and the forward thinking plan for new products still on track. They did this to create room for see sawing sales and unexpected costs. If you investigate a lot of the early watch manufacturers they show modest or significant investment in the beginning. They show steady or moderate growth then simply go out of business. The reason or lack of reasons given are generally funding was not adequate because the proprietor failed to secure additional investment or failed to account for all of the expected incurrence. Investors then and now will pull out at the first sign of mismanagement or market destabilization. To summarize this discussion, material while not significant as a listed cost compared to labor was often used to "hedge" the future and allow portability to a given point. That is why the manufacturers frequently overproduced and filled special requests in this fashion. The smart proprietor knew when he had enough inventory to carry him through. This early standardization was an important step, but the issue was accountability in house. Just in time is essentially what the Swiss do now and they leverage costs in this manner. Early American manufacturers simply mismanaged their business. Viele Grüße David Fahrenholz Fahrenholz Clock & Watch Timeless Service | ||||

|

| IHC Member 163 |

Up to the last decade or so, U.S. industry used to use post in their annual report the amount of inventory on hand as a plus. Since the introduction of JIT, or just in time inventory management, it was recognized that static inventory was actually a negative on the books, rather than a positive. Using that, it makes perfect sense to me regarding the literally thousands of extra parts that were reported to be on a companies shelves as something that a company didn't view as a detriment to the bottom line. Nobody did until the 1980s! Regards. Mark NAWCC Member 157508 NAWCC-IHC Member 163 | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Your request is being processed... |

|

©2002-2025 Internet Horology Club 185™ - Lindell V. Riddle President - All Rights Reserved Worldwide