| WWT Shows | CLICK TO: Join and Support Internet Horology Club 185™ | IHC185™ Forums |

|

• Check Out Our... • • TWO Book Offer! • |

Welcome Aboard IHC185™  Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers

Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers  Pocket Watch Discussions

Pocket Watch Discussions  Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"

Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"

Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers

Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers  Pocket Watch Discussions

Pocket Watch Discussions  Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"

Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"Go  | New Topic  | Find-Or-Search  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply to Post  |  |

| IHC Member 1555 |

Hi All, Does someone have any info about an Illinois 18s watch marked with the words "The Commodore", was it a private label and if so which Jeweller or Company ordered them? Also how many of the Grade were marked as such? The watch in question is a Grade 64 adjusted 17 Jewel serial# 1421630. Thanks to All. Regards, Bila | ||

|

| IHC Life Member |

Bila, there were 200 movements released by Illinois in the batch that your "The Commodore" was included with. How many of these were Commodores is not detailed by my source. A total of 16,502 Grade 64 were produced with most being "OEM", or "Private Label" watches for various Jewelers and Sears. This could have been a special treatment for Sears, but as the Dial was also supposed to be signed "Commodore" I must admit that is only speculation. Illinois also produced some "The Commodore"'s as Hunter movements. | |||

|

| IHC Member 1555 |

Thanks David, the dial on this one is marked with "The Commodore" as well. Do you know if these are the same as the Commodore Perry watch Regards, Bila | |||

|

| IHC Life Member |

Bila, the "Commodore Perry" was produced for resale by E. Cohen & Co., Erie, PA. The models Illinois produced for them were a RRG 18s Gr103 15J (Hunter) & 16J (5th pinion OF conv.); 12s open and Hunter 21J (A Lincoln Mvt.) & 17J Gr. 405. Quite different from "The Commodore" you won at a GREAT PRICE! The dial alone is worth more! Good luck with the restoration!  | |||

|

| IHC Member 1555 |

Thanks once again David for your knowledge, very much appreciated. I will give it a nice restoration in the coming months as I am snowed under at present. Should turn out very nice indeed. Cheers, Bila | |||

|

| IHC Member 1291 |

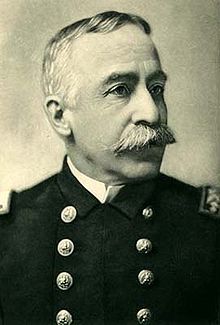

I have heard tale and believe this watch was in tribute to Commodore George Dewey. I will have to make this a long post in this thread in order for you to see the importance and significance of the "Commodore"; Between 1895 and 1898 Cuba and the Philippine Islands revolted against Spain. The Cubans gained independence, but the Filipinos did not. In both instances the intervention of the United States was the culminating event. In 1895 the Cuban patriot and revolutionary, Jose' Marti' resumed the Cuban struggle for freedom that had failed during the Ten Years' War (1868-1878). Cuban juntas provided leadership and funds for the military operations conducted in Cuba. Spain possessed superior numbers of troops, forcing the Cuban generals Maximo Gomez and Antoneo Maceo, to wage guerrilla warfare in the hope of exhausting the enemy. Operations began in southeastern Cuba but soon spread westward. The Spanish Conservative Party, led by Antonio Cánovas y Castillo, vowed to suppress the insurrectos, but failed to do so. The Cuban cause gained increasing support in the United States, leading President Grover Cleveland to press for a settlement, but instead Spain sent General Valeriano Weyler to pacify Cuba. His stern methods, including reconcentration of the civilian population to deny the guerrillas support in the countryside, strengthened U.S. sympathy for the Cubans. President William McKinley then increased pressure on Spain to end the affair, dispatching a new minister to Spain for this purpose. At this juncture an anarchist assassinated Canovas, and his successor, the leader of the Liberal Party Praxedes Mateo Sagasta , decided to make a grant of autonomy to Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Cuban leadership resisted this measure, convinced that continued armed resistance would lead to independence. In February two events crystallized U.S. opinion in favor of Cuban independence. First, the Spanish minister in Washington,Enrique Dupuy de Lome, wrote a letter critical of President McKinley that fell into the hands of the Cuban junta in New York. Its publication caused a sensation, but Sagasta quickly recalled Dupuy de Lóme. A few days later, however, the Battleship Maine, which had been sent to Havana to provide a naval presence there exploded and sank, causing the death of 266 sailors. McKinley, strongly opposed to military intervention, ordered an investigation of the sinking as did Spain. The Spanish inquiry decided that an internal explosion had destroyed the vessel, but the American investigation claimed an external source. The reluctant McKinley was then forced to demand that Spain grant independence to Cuba, but Sagasta refused, fearing that such a concession would destroy the shaky Restoration Monarchy. It faced opposition from various domestic political groups that might exploit the Cuban affair by precipitating revolution at home. Underlying strong Spanish opposition to Cuban freedom was the traditional belief that God had granted Spain its empire, of which Cuba was the principal remaining area, as a reward for the conquest of the Moors. Spanish honor demanded defense of its overseas possessions, including Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Spain sought diplomatic support from the great powers of Europe, but its long-standing isolation and the strength of the U.S. deterred sympathetic governments from coming to its aid. On 25 April Congress responded to McKinley's request for armed intervention. Spain had broken diplomatic relations on 23 April. The American declaration of war was predated to 21 April to legitimize certain military operations that had already taken place, particularly a blockade of Havana. To emphasize that its sole motive at the beginning of the struggle was Cuban independence, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution, the Teller Amendement, that foreswore any intention of annexing Cuba. Neither nation had desired war but both had made preparations as the crisis deepened after the sinking of the Maine. McKinley, having opposed war, hoped to end it quickly at the least possible expenditure of blood and treasure. The U.S. possessed a small well-trained navy, but the army was composed only twenty-eight thousand regulars. Spain had large garrisons in Cuba and the Philippines, but its navy was poorly maintained and much weaker than that of the U.S. Prewar planning in the U.S. had settled upon a naval blockade of Cuba and an attack on the decrepit Spanish squadron at Manila to achieve command of the sea and preclude reinforcement and resupply of the Spanish overseas forces. These measures would bring immediate pressure on Spain and signal American determination. The small army would conduct raids against Cuba and help sustain the Cuban army until a volunteer army could be mobilized for extensive service in Cuba. Spain was forced to accept the U.S. decision to fight on the periphery of Spanish power where its ability to resist was weakest. The war began with two American successes. Admiral William Sampson immediately established a blockade of Havana that was soon extended along the north coast of Cuba and eventually to the south side. Sampson then prepared to counter Spanish effort to send naval assistance. Then, on 1 May, Commodore George Dewey, commanding the Asiatic Squadron, destroyed Admiral Patricio Montoyo's small force of wooden vessels in Manila Bay. Dewey had earlier moved from Japan to Hong Kong to position himself for an attack on the Philippines. When news of this triumph reached Washington, McKinley authorized a modest army expedition to conduct land operations against Manila, a step in keeping with the desire to maintain constant pressure on Spain in the hope of forcing an early end to the war. On 29 April a Spanish squadron commanded by Admiral Pascual Cervera left European waters for the West Indies to reinforce the Spanish forces in Cuba. Sampson prepared to meet this challenge to American command of the Caribbean Sea. Cervera eventually took his squadron into the harbor at Santiago de Cuba at the opposite end of the island from Havana where the bulk of the Spanish army was concentrated. As soon as Cervera was blockaded at Santiago (29 May) McKinley made two important decisions. He ordered the regular army, then being concentrated at Tampa, to move as quickly as possible to Santiago de Cuba. There it would join with the navy in operations intended to eliminate Cervera's forces. Also on 3 June he secretly informed Spain of his war aims through Great Britain and Austria. Besides independence for Cuba, he indicated a desire to annex Puerto Rico (in lieu of a monetary indemnity) and an island in the Marianas chain in the Pacific Ocean. Also the United States sought a port in the Philippines, but made no mention of further acquisitions there. The American message made it clear that the U.S. would increase its demands, should Spain fail to accept these demands. Sagasta was not yet ready to admit defeat, which ended the initial American attempt to arrange an early peace. Major General William Shafter then conducted a chaotic but successful transfer of the Fifth Army Corps from Tampa to the vicinity of Santiago de Cuba. The need to move quickly caused great confusion, but it was a reasonable price to pay for seizing the initiative at the earliest possible moment. The navy escorted his convoy of transports around the eastern end of Cuba to Santiago de Cuba, where he arrived on 20 June. After landing at Daiquiri and Siboney east of the city, he moved quickly toward the enemy along an interior route, fearful of tropical diseases and desirous of thwarting Spanish reinforcements on the way from the north. The navy urged a different course, suggesting an attack on the narrow channel connecting the harbor of Santiago de Cuba to the sea. An advance near the coast would allow the navy's guns to provide artillery support. Sweeping of mines in the channel and seizure of the batteries in the area would enable the navy to storm the harbor entrance and enter the harbor for an engagement with Cervera's forces. Shafter rejected this proposal, perhaps because of army-navy rivalry. The Spanish commander did not oppose Shafter's landing and offered only slight resistance to his westward movement. He disposed his garrison of ten thousand men along a perimeter reaching entirely around the city to the two sides of the harbor channel, hoping to prevent Cuban guerrillas under General Maximo Gomez from getting into the city. Three defensive lines were created west of the city to deal with the American advance. The first line was centered on the San Juan Heights, but only five hundred troops were assigned to defend the place. The Spanish intended to make their principal defense closer to the city. Shafter's plan of attack, based on inadequate reconnaissance, envisioned two associated operations. One force would attack El Caney, a strong point of the Spanish left to eliminate the possibility of a flank attack on the main American effort, aimed at the San Juan Heights. After reducing El Caney, the American troops would move into position to the right of the rest of the Fifth Corps for an assault in the San Juan Heights that would carry into the city and force the capitulation of the Spanish garrison. Shafter's orders for the attack were vague, leading some historians to believe that Shafter intended only to seize the heights. The battle of 1 July did not develop as planned. Lawton's force was detained at El Caney where a Spanish garrison of only five hundred men held off the attackers for many hours. Meanwhile the rest of the Fifth Corps struggled into position beneath the San Juan Heights. It did not move against the Spanish positions until the early afternoon. Fortunately a section of Gatling guns was able to fire on the summit of San Juan Hill, a bombardment that forced the Spanish defenders to abandon the position to the American force attacking on the left. Another group on the right that included the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, commanded that day by Theodore Roosevelt, moved across an adjacent elevation, Kettle Hill. The Spanish retreated to their second line of defense, and the Fifth Army Corps, exhausted and disorganized, set about entrenching itself on the San Juan Heights. Having failed to seize the city, Shafter considered abandoning this position, which was exposed to enemy artillery fire, but mandatory orders from Washington led instead to the inauguration of a siege, soon supported by the arrival of U.S. reinforcements. The partial success of 1 July produced consternation in Havana. The commander in Cuba, General Ramon Blanco, ordered Cervera to leave Santiago de Cuba, fearing that the Spanish squadron would fall into American hands, to face the concentrated fire of all the American vessels outside, a certain recipe for disaster. Blanco persisted, and on 3 July Cervera made his sortie. Admiral Sampson had just left the blockade, moving east to compose differences with General Shafter. This movement left Commodore Winfield Scott Schley as the senior officer present during the naval battle. Schley had earned Sampson's distrust because of his earlier failure to blockade Cervera promptly. This concern was justified when Schley allowed his flagship to make an eccentric turn away from the exiting Spanish ships before assuming its place in the pursuit. Cervera hoped to flee west to Cienfuegos, but four of his five vessels were sunk near the entrance to the channel. The other ship was overhauled over fifty miles westward where its commander drove it upon the shore to escape sinking. This destruction of Cervera's squadron decided the war, although further fighting occurred elsewhere. Sagasta decided to capitulate at Santiago de Cuba and to inaugurate peace negotiations at an early date through the good offices of France. He also recalled a naval expedition under Admiral Manuel de la Cámara that had left Spain earlier, moving eastward through the Mediterranean Sea and the Suez Canal to relieve the garrison in the Philippines. The navy had organized a squadron to pursue Cámara, but his recall ended any requirement for it. After the Spanish forces at Santiago de Cuba capitulated on 17 July, a welcome event because the Fifth Army Corps had fallen victim to malaria, dysentery, and other tropical diseases, the Commanding General of the Army, Nelson Miles, led an expedition to Puerto Rico that landed on the south coast of that island. He sent three columns northward with orders to converge on San Juan. These movements proceeded successfully, but were ended short of the objective when word of a peace settlement reached Miles. Meanwhile the fifth Army Corps was hastily shipped to Long Island to recuperate while volunteer regiments continued the occupation of Cuba commanded by General Leonard Wood. The last military operations of the war were conducted at Manila. An expedition under Major General Wesley Merritt arrived during July and encamped north of the city. Preparations for an attack were made amidst increasing signs of opposition from Filipino insurrectos led by Emelio Aguinaldo. He had become the leader of a revolutionary outburst in 1896-1897 that had ended in a truce. He established himself in Hong Kong, and in May 1898 Commodore Dewey transported him to Manila where he set about re-energizing his movement. During the summer he succeeded in gaining control of extensive territory in Luzon, and his forces sought to seize Manila. Dewey provided some supplies, but did not recognize the government that Aguinaldo set up. Dewey hoped to avoid further hostilities at Manila. To this end he engaged in shadowy negotiations with a new Spanish governor in Manila and the Roman Catholic Bishop of the city. An agreement was reached whereby there would be a brief engagement between the Spanish and American forces followed immediately by surrender of the city, after which the Americans were to prevent Aguinaldo's troops from entering Manila. General Merritt was suspicious of this deal, but on 13 August, after the American troops moved through a line of defenses north of Manila, the Spanish garrison surrendered to Dewey. The guerrillas were denied access, and the American troops occupied the city. Continuing American failure to recognize the Aguinaldo government fostered increasing distrust. Meanwhile, negotiations between McKinley and the French ambassador in Washington, Jules Cambon, came to fruition. The string of Spanish defeats ensured that the U.S. could dictate a settlement. On 12 August, McKinley and Cambon signed a protocol that provided for Cuban independence and the cession of Puerto Rico and an island in the Marianas (Guam). It differed from the American offer of June only in that it deferred action on the Philippines to a peace conference in Paris. The cautious McKinley hoped to limit American involvement with the Philippines, but a strong current of public opinion in favor of the annexation of the entire archipelago forced the President's hand. He developed a rationale for expansion that stressed the duty of the nation and its destiny, arguing that he could discern no other acceptable course. The Spanish delegation at the peace conference was forced to accept McKinley's decision. The Treaty of Paris signed on 10 December 1898 ceded the Philippines to the U.S. in return for a sum of $25 million to pay for Spanish property in the islands. When the treaty was sent to the Senate for approval, anti-imperialist elements offered some opposition, but on 6 February 1899 the Senate accepted it by a vote of 57 to 27, only two more than the necessary two-thirds majority. Fatefully, two days before the vote, armed hostilities broke out at Manila between the American garrison and Aguinaldo's troops, the beginning of a struggle that lasted until July 1902. Although Cuba received its independence, the Platt Amendement (1902) severely limited its sovereignty and stimulated a dependent relationship that affected the evolution of Cuban society. This dependency leads some historians to maintain that the events of 1895-1898 were simply a transition (la transición) from Spanish imperialism to American imperialism. Eventually the U.S. rejected the expansion of 1898, which included the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands, canceling the Platt Amendment, granting independence to the Philippine Islands, and admitting Hawaii into the Union. The war heralded the emergence of the United States as a great power, but mostly it reflected the burgeoning national development of the nineteenth century. World War I, not the American intervention in the Cuban-Spanish struggle of 1895-1898, determined the revolutionized national security policy of the years since 1914. These policies, in keeping with American values, were decidedly anti-imperialistic in both the formal and informal meanings of the term. During the Spanish-American War, on June 12, 1898 Filipino rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed the independence of the Philippines after 300 years of Spanish rule. By mid-August, Filipino rebels and U.S. troops had ousted the Spanish, but Aguinaldo's hopes for independence were dashed when the United States formally annexed the Philippines as part of its peace treaty with Spain. The Philippines, a large island archipelago situated off Southeast Asia, was colonized by the Spanish in the latter part of the 16th century. Opposition to Spanish rule began among Filipino priests, who resented Spanish domination of the Roman Catholic churches in the islands. In the late 19th century, Filipino intellectuals and the middle class began calling for independence. In 1892, the Katipunan, a secret revolutionary society, was formed in Manila, the Philippine capital on the island of Luzon. Membership grew dramatically, and in August 1896 the Spanish uncovered the Katipunan's plans for rebellion, forcing premature action from the rebels. Revolts broke out across Luzon, and in March 1897, 28-year-old Emilio Aguinaldo became leader of the rebellion. By late 1897, the revolutionaries had been driven into the hills southeast of Manila, and Aguinaldo negotiated an agreement with the Spanish. In exchange for financial compensation and a promise of reform in the Philippines, Aguinaldo and his generals would accept exile in Hong Kong. The rebel leaders departed, and the Philippine Revolution temporarily was at an end. In April 1898, the Spanish-American War broke out over Spain's brutal suppression of a rebellion in Cuba. The first in a series of decisive U.S. victories occurred on May 1, 1898, when the U.S. Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey annihilated the Spanish Pacific fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines. From his exile, Aguinaldo made arrangements with U.S. authorities to return to the Philippines and assist the United States in the war against Spain. He landed on May 19, rallied his revolutionaries, and began liberating towns south of Manila. On June 12, he proclaimed Philippine independence and established a provincial government, of which he subsequently became head. His rebels, meanwhile, had encircled the Spanish in Manila and, with the support of Dewey's squadron in Manila Bay, would surely have conquered the Spanish. Dewey, however, was waiting for U.S. ground troops, which began landing in July and took over the Filipino positions surrounding Manila. On August 8, the Spanish commander informed the United States that he would surrender the city under two conditions: The United States was to make the advance into the capital look like a battle, and under no conditions were the Filipino rebels to be allowed into the city. On August 13, the mock Battle of Manila was staged, and the Americans kept their promise to keep the Filipinos out after the city passed into their hands. While the Americans occupied Manila and planned peace negotiations with Spain, Aguinaldo convened a revolutionary assembly, the Malolos, in September. They drew up a democratic constitution, the first ever in Asia, and a government was formed with Aguinaldo as president in January 1899. On February 4, what became known as the Philippine Insurrection began when Filipino rebels and U.S. troops skirmished inside American lines in Manila. Two days later, the U.S. Senate voted by one vote to ratify the Treaty of Paris with Spain. The Philippines were now a U.S. territory, acquired in exchange for $20 million in compensation to the Spanish. In response, Aguinaldo formally launched a new revolt--this time against the United States. The rebels, consistently defeated in the open field, turned to guerrilla warfare, and the U.S. Congress authorized the deployment of 60,000 troops to subdue them. By the end of 1899, there were 65,000 U.S. troops in the Philippines, but the war dragged on. Many anti-imperialists in the United States, such as Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, opposed U.S. annexation of the Philippines, but in November 1900 Republican incumbent William McKinley was reelected, and the war continued. On March 23, 1901, in a daring operation, U.S. General Frederick Funston and a group of officers, pretending to be prisoners, surprised Aguinaldo in his stronghold in the Luzon village of Palanan and captured the rebel leader. Aguinaldo took an oath of allegiance to the United States and called for an end to the rebellion, but many of his followers fought on. During the next year, U.S. forces gradually pacified the Philippines. In an infamous episode, U.S. forces on the island of Samar retaliated against the massacre of a U.S. garrison by killing all men on the island above the age of 10. Many women and young children were also butchered. General Jacob Smith, who directed the atrocities, was court-martialed and forced to retire for turning Samar, in his words, into a "howling wilderness." In 1902, an American civil government took over administration of the Philippines, and the three-year Philippine insurrection was declared to be at an end. Scattered resistance, however, persisted for several years. More than 4,000 Americans perished suppressing the Philippines--more than 10 times the number killed in the Spanish-American War. More than 20,000 Filipino insurgents were killed, and an unknown number of civilians perished. In 1935, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established with U.S. approval, and Manuel Quezon was elected the country's first president. On July 4, 1946, full independence was granted to the Republic of the Philippines by the United States. George Dewey Born December 26, 1837 Montpelier, Vermont Died January 16, 1917 (aged 79) Washington, D.C. Place of burial Washington National Cathedral Allegiance United States of America Union Service/branch United States Navy Years of service 1858–1917 Rank Admiral of the Navy Commands held Asiatic Squadron General Board of the United States Navy Battles/wars; American Civil War Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip Battle of New Orleans Battle of Port Hudson First Battle of Fort Fisher Second Battle of Fort Fisher Spanish-American War Battle of Manila Bay regards, bb  | |||

|

Commodore George Dewey is the only Naval Officer to hold the Rank of Admiral of the Navy which out ranks all other Navy Admirals, Fleet Admirals included. The only other Military Officer with equal rank was General of the Armies John J.Pershing who also out ranks all other Army Generals. In 1976 George Washington was given the Rank of General of the Armies of the United States which out ranks them all. | ||||

|

| IHC Member 1555 |

Thanks Buster & Michael for the very interesting history, I was ignorant of this history with regard to the Philippines Buster, I am glad that you took the time to give such a detailed post. Best Regards, Bila | |||

|

| IHC Member 1955 |

Exceptional history, Buster. It's of particular interest to me because my grandfather, Felix McNamee, served in the US Army during the Spanish-American War. I myself served in the PI in the early 1980s on board USS BERKELEY (DDG-15) and USS KISKA (AE-35), but that's another story . . . These days, I'm just waiting for legal access to the Cohiba of my choosing From my naval training, I know Michael is right--Commodore Dewey was our only Admiral of the Navy. Mike | |||

|

Thanks Buster I really enjoyed that, it's nice to know a bit of history behind a name Ken | ||||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Your request is being processed... |

|

Welcome Aboard IHC185™  Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers

Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers  Pocket Watch Discussions

Pocket Watch Discussions  Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"

Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"

Internet Horology Club 185

Internet Horology Club 185  IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page

IHC185™ Discussion Site Main Page  Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers

Horological Discussions, Questions and Answers  Pocket Watch Discussions

Pocket Watch Discussions  Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"

Info on Illinois Grade 64 "The Commodore"©2002-2025 Internet Horology Club 185™ - Lindell V. Riddle President - All Rights Reserved Worldwide